Hikes in Philippine History #4: German explorer Fedor Jagor’s finale in Bicol: Mt. Mayon in 1859

|

| Mason Volcano, the finale of the four mountains in Bicol that German explorer Fedor Jagor hiked in 18 |

annotated by Gideon Lasco

In the course of my historical research I have stumbled upon various accounts of mountain climbing trips in the journals of hikes in the Philippines – or at least descriptions of various mountains. They are too interesting to ignore so I thought it would be nice to start a series about them.

|

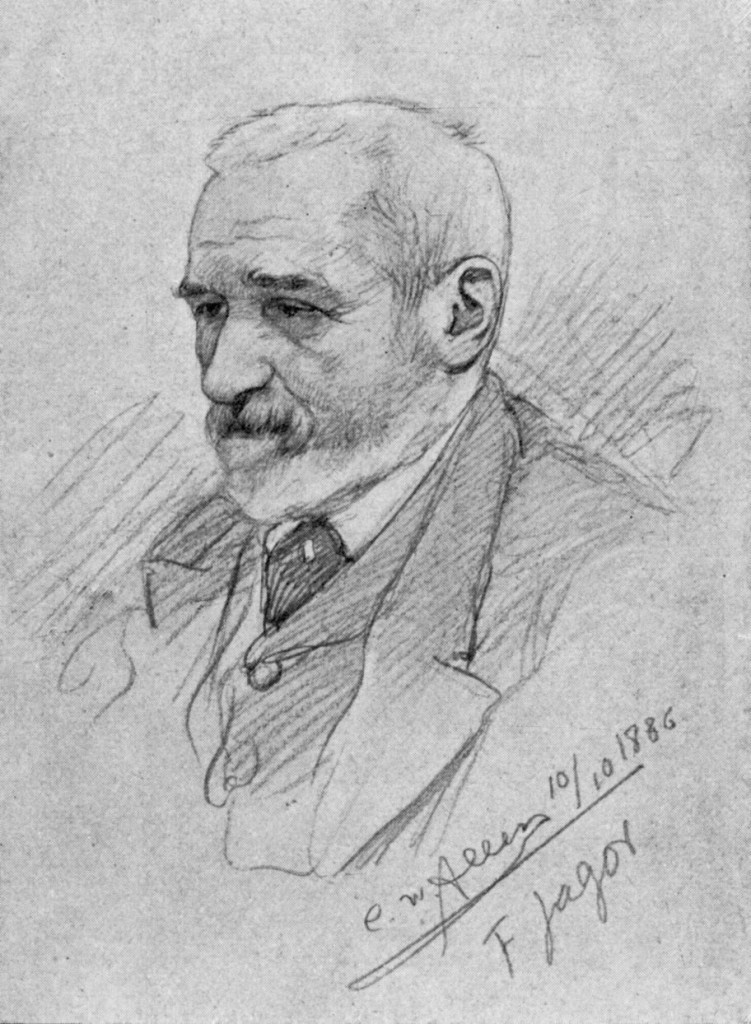

| Fedor Jagor (1816-1900) |

The first featured hiker on our list is Fedor Jagor

(1816–1900), a German scientist and explorer who traveled in the Philippines from 1859-1860. This account, originally in German and later translated in English, is probably the first to describe hikes up Bicol mountains. After three mountains (Isarog, Asog, Masaraga), this is his finale: no less than beautiful Mayon Volcano!

MT. MAYON

My Spanish friends enabled me to rent a house in Daraga,1 a well-to-do town of twenty thousand inhabitants at the foot of the Mayon, a league and a half from Legaspi. The summit of this volcano was considered inaccessible until two young Scotchmen, Paton and Stewart by name, demonstrated the contrary. Since then several natives have ascended the mountain, but no Europeans.

We reached the summit about one o’clock. It was covered with fissures which gave out sulphurous gases and steam in such profusion that we were obliged to stop our mouths and nostrils with our handkerchiefs to prevent ourselves from being suffocated. We came to a halt at the edge of a broad and deep chasm, from which issued a particularly dense vapor. Apparently we were on the brink of a crater, but the thick fumes of the disagreeable vapor made it impossible for us to guess at the breadth of the fissure.

The absolute top of the volcano consisted of a ridge, nearly ten feet thick, of solid masses of stone covered with a crust of lava bleached by the action of the escaping gas. Several irregular blocks of stone lying about us showed that the peak had once been a little higher. When, now and again, the gusts of wind made rifts in the vapor, we perceived on the northern corner of the plateau several rocky columns at least a hundred feet high, which had hitherto withstood both storm and eruption. I afterwards had an opportunity of observing the summit from Daraga with a capital telescope on a very clear day, when I noticed that the northern side of the crater was considerably higher than its southern edge.

Our descent took some time. We had still two-thirds of it beneath us when night overtook us. In the hope of reaching the hut where we had left our provisions, we wandered about till eleven o’clock, hungry and weary, and at last were obliged to wait for daylight. This misfortune was owing not to our want of proper precaution, but to the unreliability of the carriers. Two of them, whom we had taken with us to carry water and refreshments, had disappeared at the very first; and a third, “a very trustworthy man,” whom we had left to take care of our things at the hut, and who had been ordered to meet us at dusk with torches, had bolted, as I afterwards discovered, back to Daraga before noon.

My servant, too, who was carrying a woolen blanket and an umbrella for me, suddenly vanished in the darkness as soon as it began to rain, and though I repeatedly called him, never turned up again till the next morning. We passed the wet night upon the bare rocks, where, as our very thin clothes were perfectly wet through, we chilled till our teeth chattered. As soon, however, as the sun [88]rose we got so warm that we soon recovered our tempers. Towards nine o’clock we reached the hut and got something to eat after twenty-nine hours’ fast.

I learnt from Mr. Paton that the undertaking had also been represented as impracticable in Albay. “Not a single Spaniard, not a single native had ever succeeded in reaching the summit; in spite of all their precautions they would certainly be swallowed up in the sand.” However, one morning, about five o’clock, they set off, and soon reached the foot of the cone of the crater. Accompanied by a couple of natives, who soon left them, they began to make the ascent. Resting half way up, they noticed frequent masses of shining lava, thrown from the mouth of the crater, gliding down the mountain. With the greatest exertions they succeeded, between two and three o’clock, in reaching the summit, where, however, they were prevented by the noxious gas from remaining more than two or three minutes. During their descent, they restored their strength with some refreshments Sr. Muñoz had sent to meet them; and they reached Albay towards evening, where during their short stay they were treated as heroes, and presented with an official certificate of their achievement, for which they had the pleasure of paying several dollars.

Blogger’s note: In this dayhike-turned-overnight hike, Jagor describes Mayon very similarly to how a hike of it will look like today. He had a hard time. Later in his diary he would write: “I sprained my foot so badly in ascending Mayon that I was obliged to keep the house for a month.”

Reference: The Former Philippines Through Foreign Eyes (Craig, 1917 ed.). Available: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10770/10770-h/10770-h.htm#xd20e3939

FEDOR JAGOR’S HIKES IN BICOL (1859-1860)

Hiking in Philippine history #1: Mt. Isarog

Hiking in Philippine history #2: Mt. Asog

Hiking in Philippine history #3: Mt. Masaraga

Hiking in Philippine history #4: Mt. Mayon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!